[ad_1]

Now starting to (but just a little).

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

There have been countless layoff announcements, some of them by big tech and social media companies, others from perennially money-losing companies that suddenly have to preserve cash – such as by BuzzFeed earlier this week to lay off 12% of its staff, or today by meal-delivery-penny-stock Blue Apron to lay off 10% of its corporate staff. Most of the announced layoffs were in the hundreds. Some were bigger, such as Meta with 11,000; and Twitter, a total mess of layoffs, quits, and please-come-backs. But they’re still small-ish numbers compared to the 153.5 million total employees in the US.

But there is still a historically huge number of job openings. Even as some workers in tech and social media companies are laid off, industrial companies, automakers (they’re investing heavily to build their EV divisions), and others are desperately trying to hire tech workers.

Ford, for example, is trimming its workforce in its legacy divisions, where sales are sagging, but is hiring tech and engineering talent in its EV division, where sales are booming, and where it has to start everything from scratch, including designing and building vehicles, software, supply chains, factories, etc. These companies have been starved of tech talent because they couldn’t compete with the rich pay packages and stock options offered by the likes of Twitter or Meta. But now they might be able to attract talent.

Layoff announcements by US companies are global layoffs, and some of these layoffs hit staff in other countries. For example, Twitter’s layoff numbers included its layoffs in India, where it gutted its office. Twitter also cancelled thousands of contractors, many of them in other countries.

Then there are the H-1B visa holders. Tech and social media companies, and other companies with tech divisions, are heavily staffed with people from other countries that are in the US on H-1B visas. And the layoff announcements include them. But these folks only have 60 days to find another employer after their current employment ends. If they cannot, they’re considered “out of status” and in theory would have to leave the US.

When workers on an H-1B visa get laid off, they’re not eligible for unemployment compensation in the US, and so they’re not showing up in the unemployment insurance claims that we’re going to look at.

And once they’re leaving the country, they no longer show up as “unemployed” in the monthly jobs report.

These are among the reasons why we haven’t seen a big increase in the weekly claims for unemployment insurance by the Labor Department.

But the trend has changed direction, as the “continued claims” (unemployment insurance claims by people who haven’t yet found a job at least one week after their initial claim) are now solidly increasing, though remain historically low.

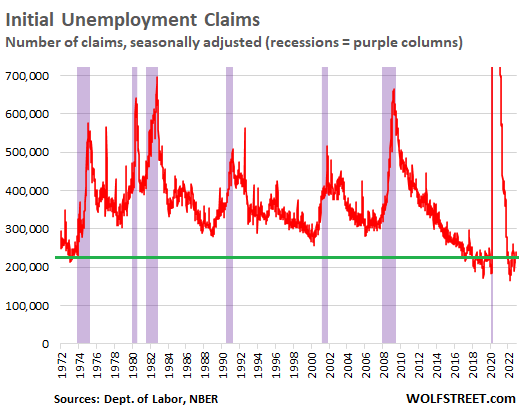

Initial claims for unemployment insurance: 230,000 people filed an initial claim for unemployment insurance with their state unemployment offices in the week through Saturday, according to the Labor Department today. This was in the same low range as in prior weeks (up a little from last week, down a little from the prior week) and in the same low range as before the pandemic:

The long view of initial claims for unemployment insurance shows just how low they still are. For the labor market to soften meaningfully, we would have to see the number of initial unemployment claims rise above the 300,000 mark. When recessions occurred (purple columns), the number of initial weekly claims was spiking through the 350,000 range.

This shows that most of the people who got laid off found a job so quickly or already had a new job waiting in the wings that they didn’t need to file for unemployment compensation.

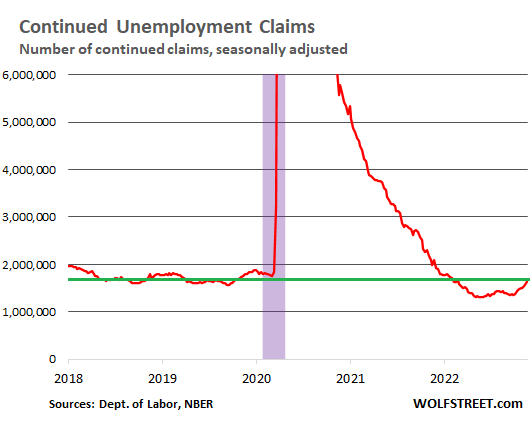

But some people now have a harder time finding a new job. The number of people who are still claiming unemployment insurance at least one week after the initial claim – people who haven’t yet found another job – rose to 1.67 million, according to the Labor Department today.

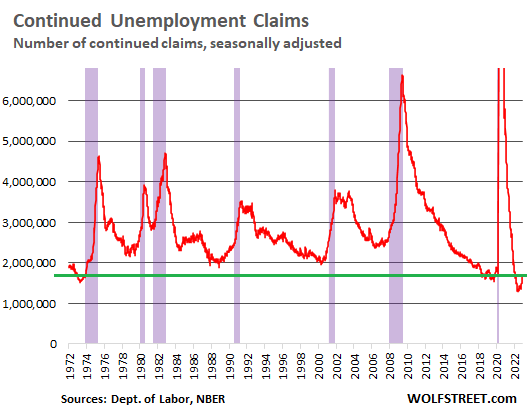

This is still historically low, about as low as during the lowest points just before the pandemic, and way lower than anything since the mid-1970s (when there were many fewer working people).

But it does show that the trend has solidly reversed, that some people are having a harder time finding a new job, and that they stay on unemployment insurance a little longer. This is a sign that the labor market is getting a little less tight:

This is the short view:

The long view shows just how historically low the 1.67 million continued claims are. But it also shows that the trend is now rising, having solidly reversed course. During the mild recession in 2001, these continued claims rose as high as 3.7 million. During the Great Recession, they jumped to 6.6 million.

We’ve had other indications that the labor market is getting just a little less tight, but remains very tight. The weekly unemployment insurance claims are the timeliest data we have. And they depict a labor market that is still amazingly tight, given all the layoff announcements, but is starting to loosen up a little to where some of the people who lost their jobs – and they might not be tech workers – are having to look a little longer to find a new job and remain on unemployment insurance just a little longer.

To stick with the “soft landing” analogy, the labor market is not landing at all yet, but it’s losing a little altitude.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from wolfstreet.com. Read the original article here.